Once more unto the breach: ASIC finalises its guidance for the new breach reporting regime

ASIC has now published its updated and final guidance on the new breach reporting regime for AFS and credit licensees that will apply from 1 October 2021.[1] This article highlights:

- how the regime will operate and what decisions need to be taken to comply with it.

- key parts of ASIC’s updated guidance.

- practical issues for licensees.

- the legal support that Hall & Wilcox can provide.

A summary of the breach reporting regime

ASIC regards the breach reporting regime as one of the most important ways in which it obtains information on compliance and misconduct issues within licensees that enables it to decide which matters to prioritise for regulatory and enforcement action.

ASIC has long been frustrated by what it regards as inadequate and delayed breach reporting by licensees and the deficiencies in the current regime that prevent it from being enforced effectively.

The new breach reporting regime expands the scope of the existing regime under s912D of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth), by requiring a wider set of actual or potential breaches to be reported to ASIC in a more detailed, prescribed form and for this to take place within 30 days. Non-compliance is a strict liability criminal offence and a civil penalty provision.

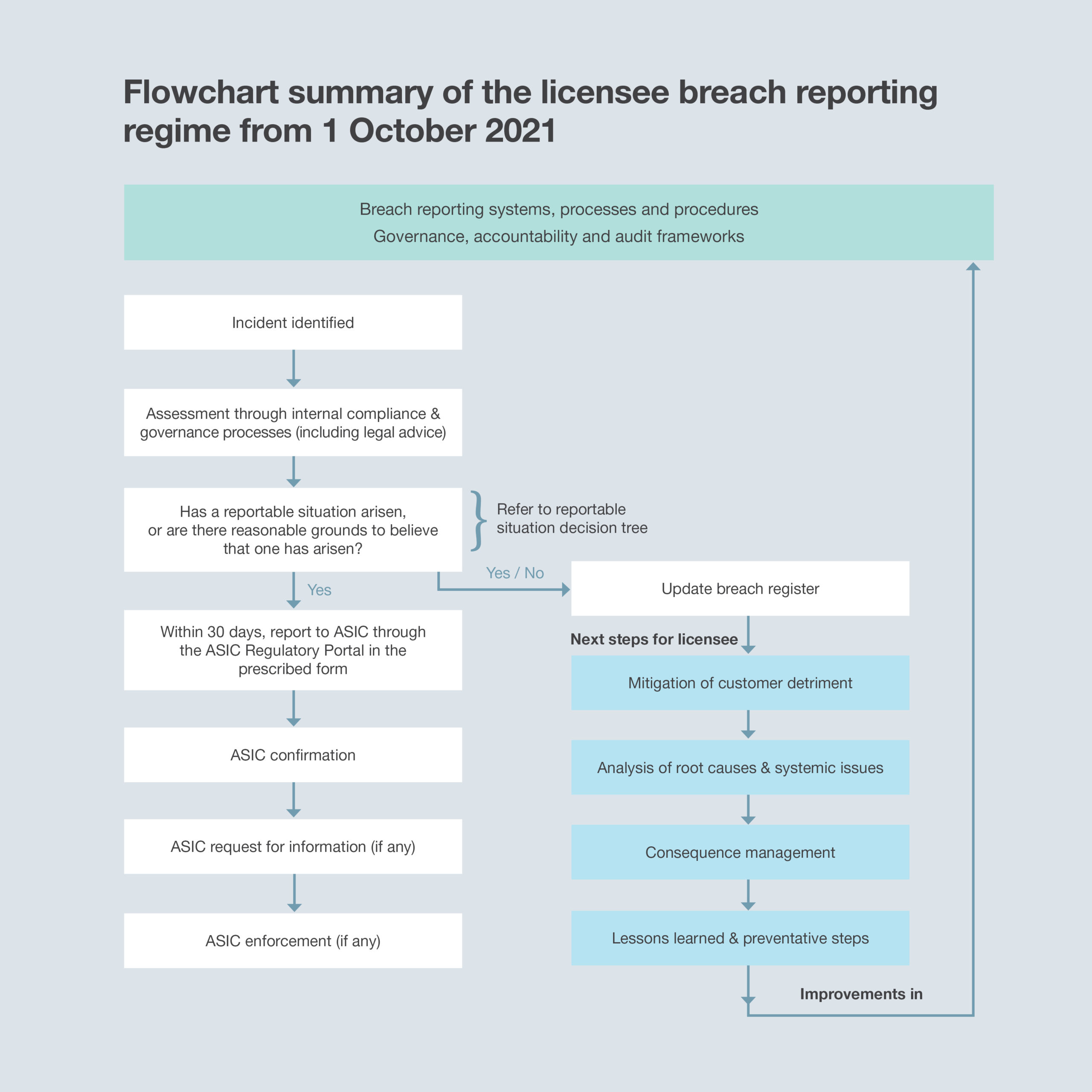

The various stages of the new breach reporting process and the decision-making steps involved in assessing what constitutes a ‘reportable situation’ are shown in the following flowchart and decision tree.

The key updates to ASIC’s guidance

ASIC’s updated guidance follows its consultation on a draft RG 78 that was released in April 2021, and it provides more clarity around the crux of the new regime that a 30-day reporting period commences from the date that a licensee first knows, or is reckless as to whether, there are reasonable grounds to believe that a reportable situation has arisen.

Timing and knowledge – whose knowledge, when?

The regime uses existing law which provides that the knowledge of a licensee can be established by showing that a director, employee or agent of the licensee had the requisite knowledge if this was acquired within the scope of that person’s actual or apparent authority. This means that an employee may acquire knowledge for the purpose of starting the 30-day reporting timeframe even if that person does not have formal authority to make a decision whether to lodge a breach report.

Existing reporting processes will be impacted by this front-ending of the trigger for the start of the reporting deadline. For example, it is commonplace for licensees to delegate their decision-making process to a specially constituted breach committee which receives a report from the compliance team (often with the benefit of legal advice) before voting on a resolution whether to lodge a breach report. This decision may then be escalated to a senior executive for confirmation.

The effect of the new regime will be that this process can still be used, but that in this example time will now begin to run from when the compliance team first knows there are reasonable grounds to believe a reportable situation has arisen – not from when the breach committee or a senior executive has reached or ratified a decision. It also means that a licensee cannot delay lodging a report while it establishes certainty around the reportable situation breach – such as determining actual proof of a breach, confirming the number of affected customers or establishing the amount of loss suffered.

In assessing issues of knowledge, the updated guidance states that ‘what is critical is the nature of the activities being conducted, not which team is conducting them.’ This will always be a matter of fact to determine in each case. For example, the mere identification of an issue within a licensee’s business (such as by its line 1 function) which is logged as an incident and escalated for review to a line 2 compliance team will not fix the line 1 function with knowledge if it has not assessed whether the incident could result in a reportable breach.

Investigations as reportable situations

If a licensee is unable to determine within 30 days of commencing an investigation into an incident whether it is a reportable situation, the fact of the investigation will itself be a reportable situation for notification. The outcome of the investigation, once known, will be an additional reportable situation.

ASIC has stated that it will not generally consider the following scenarios to constitute an ‘investigation’ because they are not specifically directed towards establishing the facts of a reportable situation:

- the mere receipt of a detective control, such as a customer complaint.

- any preliminary steps and fact-finding inquiries into the nature of an incident which are completed over a short timeframe and carried out as an initial response to the detective control.

- routine audits, quality assurance monitoring or other internal compliance review processes so long as they are not triggered by an incident or used to assess whether it is a reportable situation.

Reporting multiple breaches

The updated guidance confirms that a single breach report may deal with multiple reportable situations that are identical or similar or related to each other where there is a single, specific root cause. An example of a single root cause is given as an individual system error or process deficiency.

Licensees are expected to exercise their judgement in determining the appropriateness of any batch reporting of breaches while being careful to meet the 30-day reporting requirement for each reportable situation.

The ‘dobbing’ provision

For the first time, a licensee will have an obligation to report to ASIC if it becomes aware that a reportable situation has arisen in relation to another licensee that provides personal advice to retail clients.

ASIC has clarified that it does not expect licensees to take proactive steps to investigate potential reportable situations involving other licensees that it deals with in the course of its business. Rather, they are now to be obliged not to turn a blind eye to any facts that come before them through their usual practices or processes that would give them reasonable grounds to conclude that a reportable situation has arisen for another licensee.

ASIC’s expectations

ASIC considers that the high-level expectations it set out in its 2018 report into breach reporting remain relevant and should be considered by all licensees in adapting to the new regime.[2] This includes there being clear end-to-end senior accountability of breach reporting processes and procedures, and creating an environment that supports the raising of concerns about risks, prioritises investigations and remediation, and communicates transparently about incidents and breaches.

Issues for licensees

- Licensees will want to assess the application of this updated general guidance to their particular sectors and to the processes they intend to use for breach reporting under the new regime. They should bear in mind they may already be engaged in investigating incidents that will become reportable situations after 1 October.

- The impact of other statutory reporting regimes will need to be taken into account in the breach reporting processes that are developed. For example:

- the breach reporting regime operates independently of the 10-day reporting requirement to notify ASIC of any significant dealings under the design and distribution regime that commences on 5 October 2021 – but noting that a significant dealing may also constitute a reportable situation.

- for insurers and RSE licensees, the new regime will deem that ASIC has been notified of a reportable situation if the matter has been separately reported to APRA under the reporting regimes contained in the Insurance Act 1973 (Cth), the Life Insurance Act 1995 (Cth) and the Superannuation Industry (Supervision) Act 1993 (Cth). The separate carve-out for those matters that are required to be reported to APRA by auditors and actuaries of APRA-regulated entities has been maintained under the new regime.

- The significant expansion of matters that are required to be reported are expected to lead to increases in the volumes of notifications by licensees and in the amount of work for their compliance and legal teams. This is despite the welcome exemption last month of some civil penalty provisions from those that are automatically reportable (such as individual PDS disclosure issues if they are not otherwise significant breaches).[3] In turn, this will focus attention on the adequacy of processes and resourcing (itself a core obligation) in meeting ASIC’s stated expectations.

How we can help

Hall & Wilcox’s team of experts can assist by providing:

- software that operationalises a more detailed version of the decision tree, which can help identify reportable situations accurately and efficiently;

- a legal sign-off for breach reporting processes that takes into account ASIC’s final guidance;

- advice on whether a reportable situation has arisen; and

- advice on remediation, enforcement and other strategic matters arising from reportable situations.

Contact us to find out more.

[1] Regulatory Guide 78 ‘Breach reporting by AFS licensees and credit licensees’ (RG 78) and Report 698 ‘Response to Submissions on CP 340 Breach reporting and related obligations’. The new regime was enacted in December 2020, by the Financial Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response) Act 2020 (Cth).

[2] ASIC REP 594: Review of selected financial services groups’ compliance with the breach reporting obligation.

[3] Financial Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response – Breach Reporting and Remediation) Regulations 2021.