New Underwater Cultural Heritage Guidelines – consultation open

Proposed Underwater Cultural Heritage Guidelines will impose obligations on offshore development proponents and specify minimum standards to be used for identifying, assessing and managing First Nations UCH on seabeds in Commonwealth waters.

Consultation is now open on draft guidelines for archaeological assessment of First Nations Underwater Cultural Heritage (Draft Archaeological Guidelines) for projects such as offshore wind farms and related infrastructure. The Draft Guidelines, released by the Commonwealth Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water (DCCEEW), flow from the Guidelines that relate to Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH Guidelines) more generally, which were published in 2024.[1]

Consultation will close on Friday 29 November 2024. There are options to complete an online survey or lodge a submission.

Many aspects of the Draft Archaeological Guidelines, which we outline below, are very detailed, technical and prescriptive. These qualities may mean that development proponents may find that the processes for identifying and protecting First Nations UCH in proposed development areas, although obviously very important, could be overly complex, difficult or lengthy.

Similarly, First Nations organisations and Traditional Owners that will necessarily be involved in consultations and advice will need to be supported and resourced to be able to assist and advise proponents. Experience of the land-based cultural heritage management process demonstrates that resourcing is a key issue and that timelines for approval of plans are often blown out due to these constraints. We note that the Draft Archaeological Guidelines do not specify an ‘approval role’ for First Nations or Traditional Owners, for example, in terms of approving any mitigation measures or strategies employed by a proponent, for protecting any UCH. Nonetheless, our view is that the involvement of First Nations people and Traditional Owners detailed throughout the Draft Guidelines is significant.

Approximately 7000-9000 years ago, the sea level around Australia stabilised. This sea level approximately reflects the present-day level. However, for the 10,000 years before this, a series of events caused sea levels to rise rapidly. This resulted in approximately 29% of the then-Australian landmass becoming inundated – the Australian coastline receded by an average of 139km.

The submergence of such large tracts of land resulted in the inundation of archaeological sites that would have formed over 40,000-50,000 years of First Nations occupation in Australia. There is the potential for these sites to have survived in a submerged state, and the preservation and investigation of these sites could provide information on the history of human migration across the world.

This history and these reasons led to the development of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth) (UCH Act), the UCH Guidelines and now the more specific Draft Archaeological Guidelines.

The Draft Archaeological Guidelines support the UCH Act. Notably, it is an offence under section 30 of the UCH Act to engage in conduct that has (or is likely to have) an adverse impact on protected UCH,[2] including disturbance, damage and removal without a permit granted under section 23 of the UCH Act. Under section 23, the Minister may grant a permit allowing people to engage in conduct relating to UCH.

It is not explicit from the Draft Archaeological Guidelines or the UCH Act, but, in our view, it is possible that completion of the investigations and implementation of mitigation measures as outlined within the Draft Archaeological Guidelines, and perhaps the submission of a corresponding report, could be imposed as a condition of a permit issued under section 23 of the UCH Act.

The Draft Archaeological Guidelines are relevant to all proposed development within Commonwealth waters that involves potential physical impact to the seabed that may disturb, remove, or damage First Nations UCH. First Nations UCH includes any trace of human existence that has a cultural, historical or archaeological character, and is located underwater.[3]

Part 3 of the Draft Archaeological Guidelines

Part 3 provides details on First Nations engagement in UCH management. Key aspects from this Part include:

- In projects where actions may have the potential to cause adverse effects to First Nations UCH, development proponents are encouraged to undertake consultation, in a culturally appropriate way.

- Proponents are strongly encouraged to listen to First Nations views and concerns and to adapt their proposed actions accordingly, to ensure that First Nations UCH values are preserved.

- Engagement with First Nations people should occur often and ideally commence as early as possible in the life of a development project.

- First Nations people should be provided with the opportunity to be involved in and contribute to the archaeological assessment process, including desktop assessments, in-water investigations, identification of areas of sensitivity and the development of mitigation measures.

Part 4 of the Guidelines

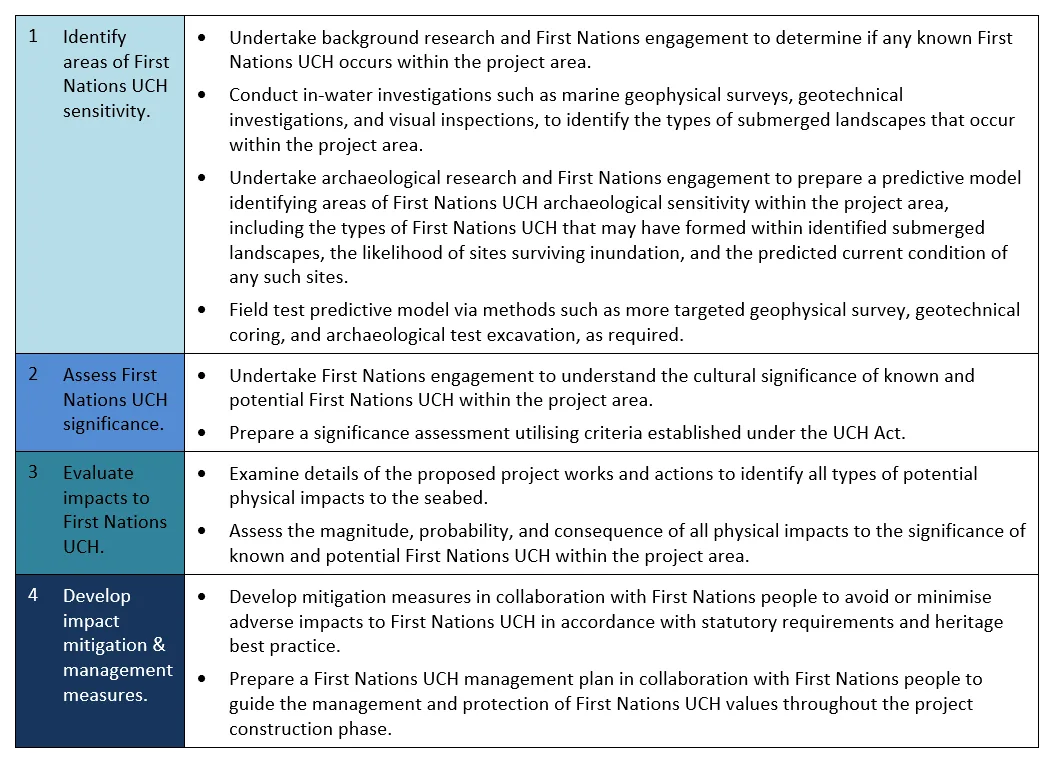

Part 4 of the Guidelines provides the framework for archaeological assessments, which includes the four steps in the table below. Technical guidance on each step is provided in Parts 5-8 in the Draft Guidelines.

Table 4.1 from the Draft Guidelines: Essential elements of a First Nations UCH Archaeological Assessment

Key aspects of the assessment process, for proponents, may include:

- Assessments should be commenced in the initial feasibility study and pre-concept design phase of a proposed nearshore or offshore development, as soon as the project area is identified.

- Proposed nearshore and offshore development projects may require one or more stages of assessment depending on a number of factors, including location of the development and extent of the proposed works. This could influence the time required to complete the assessments.

- It is the proponent’s responsibility to engage suitable practitioners for the assessment team and to co-ordinate their collaboration.

- The assessment team should, at a minimum, include archaeologists with experience in underwater archaeology and First Nations archaeology, geomorphologists with experience in marine geomorphology and First Nations people with cultural rights, interests and knowledge in the project area.

Part 5 of the Guidelines

Part 5 of the Guidelines relates to the identification of areas of First Nations UCH sensitivity within a proposed development footprint (as per Step 1 in Table 4.1, above).

Identification could involve various elements, including background research, in-water investigations (using different techniques), marine geotechnical investigations, visual inspections, test excavations and predictive modelling. Predictive modelling is aimed at identifying patterns and making predictions on the likely occurrence and condition of archaeological sites within a given area.

Our view is that the processes and investigation methods in this Part are very technical and prescriptive. The parameters for various investigation methods are very specific, including the methods used for predictive modelling. The input of an expert may be required to verify the feasibility and practicality of the various parameters.

The Draft Archaeological Guidelines do not specify an ‘approval role’ for First Nations or Traditional Owners, for example, in terms of approving mitigation measures or strategies employed by a proponent, for protecting any UCH. However, we do have concerns that there will need to be significant resources provided to First Nations organisations and Traditional Owners who will necessarily be involved in consultations and advising proponents – they will need to be supported and resourced.

Parts 6 and 7 of the Guidelines

Part 6 of the Guidelines details the process and criteria for UCH significance assessments and Part 7 of the Guidelines deals with UCH impact assessments, the purpose of which is to identify, evaluate and quantify the risk of adverse impacts to First Nations UCH, resulting from a proposed development project.

The applicable definition for adverse impact is broad. Conduct that has an adverse impact on protected UCH if the conduct:[4]

- directly or indirectly physically disturbs or otherwise damages the protected underwater cultural heritage; or

- causes the removal of the protected underwater cultural heritage from waters or from its archaeological context.

Therefore, identifying, evaluating and quantifying risks of adverse impact is likely to be a detailed and lengthy process.

Part 8 of the Guidelines

If there is a risk of adverse impact to known or potential First Nations UCH associated with a proposal, a system of impact mitigation measures and management strategies needs to be devised and implemented throughout the life of the project. Methods for designing measures and strategies and measuring their effectiveness are set out in Part 8. The fact that measures and strategies will apply throughout the life of a project suggests to us that such measures and strategies may need to extend indefinitely, depending on the lifespan of the project.

What is DCCEEW seeking feedback on?

Feedback can be provided via an online form, which includes a series of closed questions regarding the adequacy of information and detail in the Draft Guidelines. Alternatively, feedback can be provided though lodging a submission. Please get in touch if you have any questions or if you would like assistance with making a submission.

[1] Assessing and Managing Impacts to Underwater Cultural Heritage in Australian Waters: Guidelines on the application of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018.

[2] First Nations archaeological UCH located in Commonwealth waters falls under the articles listed in section 17 of the UCH Act and can be declared by the Minister for the Environment and Water as protected upon discovery and a significance assessment.

[3] Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2019 (Cth), section 15(1) defines underwater cultural heritage.

[4] Adverse impact is defined in section 30 of the Underwater Cultural Heritage Act 2018 (Cth).