Industrial relations reforms: what you need to know about what’s to come

By Fay Calderone, Paul Bonjour and Matthew Peterson

The introduction of the Fair Work Amendment (Supporting Australia’s Economic Recovery) Bill 2020 on 9 December 2020 represents what could be the biggest shake up to Australia’s industrial relations system since the commencement of the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth) on 1 July 2009. It is the culmination of a six-month period of consultation with key stakeholders including some of Australia’s largest employer groups and unions.

Industrial reform has been the subject of much contention for many years now. A lot has changed socially, economically and politically over the last decade that necessitates reform. Employers have pleaded for more flexibility to manage the modern workplace, particularly as tests for passing Enterprise Agreements became cripplingly restrictive, and Award requirements onerously prescriptive. Any suggestion of change has been met with considerable resistance by unions and assertions that it will be a slippery slope back to the days of Australian Workplace Agreements that permitted the stripping of employee pay and entitlements. Ultimately, it was the COVID-19 pandemic that gave the Morrison government a new impetus for industrial relations reform with working groups spring boarding off the collaborative approach taken with unions to introduce JobKeeper protections to manage the crisis.

In this article, our Employment team explains the key areas of reform and what businesses can expect to come in 2021.

Click on each heading below to read more about each of these areas – changes to: enterprise and greenfield agreements; casual employees; modern awards and compliance and enforcement.

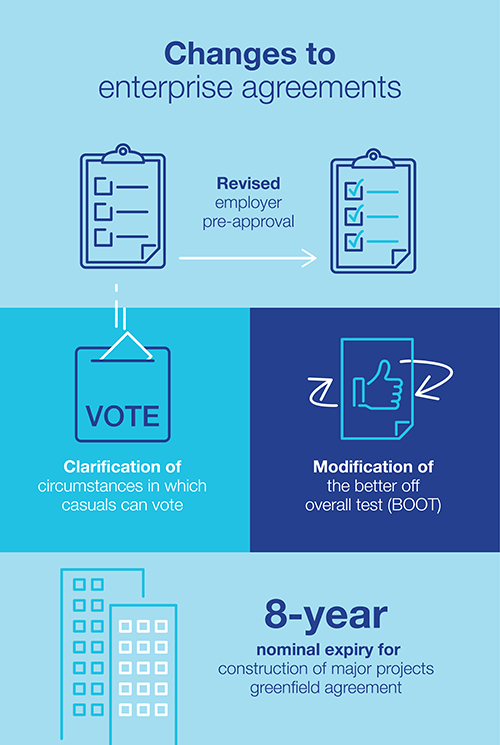

Changes to enterprise and greenfield agreements

Notice of Employee Representational Rights

Employers will now have 28 days (instead of only 14 days) to provide employees who will be covered by an enterprise agreement a notice of their right to be represented.

Modification of pre-approval requirements

The steps employers must take prior to requesting that employees vote on a proposed agreement have been replaced with a requirement that employers must take reasonable steps to ensure that relevant employees are given a fair and reasonable opportunity to decide whether or not to approve a proposed agreement.

The reasonableness of the steps to provide a fair and reasonable opportunity to decide whether or not to approve the proposed agreement will depend on the particular facts and circumstances. An employer is taken to have complied with this requirement if they take reasonable steps to ensure that:

-

- during the access period for the agreement, the relevant employees can access a copy of the proposed agreement and any other material incorporated that is not publicly available (this means that employers are not required to provide a copy of a modern award that is incorporated);

- at the start of the access period employees are notified of the time and place of the vote and the voting method that will be used; and

- the terms of the agreement, and the effect of those terms are explained to the relevant employees in an appropriate manner taking into account their particular circumstances and needs (ie cultural background, age, and whether they are represented by a bargaining representative).

Voting for casuals

Only casual employees who performed work at any time during the access period can vote on a proposed agreement or on a variation to an existing agreement.

Better off overall test

A new temporary mechanism is proposed to allow the Fair Work Commission (FWC) to approve a proposed agreement that does not pass the better off overall test (BOOT) where appropriate to do so.

When considering whether it is appropriate to do so, the FWC is required to take into account the views and circumstances of interested parties (including the likely effect of approval or non-approval), the impact of COVID-19, employee support for the proposed agreement, and whether in all the circumstances it is not contrary to the public interest.

Agreements approved under the above circumstances can only have a maximum nominal expiry of two years.

However, this proposed amendment has been criticised by the ACTU and Labor Government, with ACTU leader Sally McManus calling the changes ‘dangerous and extreme’. Given that IR Minister Christian Porter has commented that the proposed change is ‘not the most important part of the bill’, the proposed change may be abandoned to ensure the remainder of the bill passes through Parliament.

Relevant and irrelevant matters

A new subsection has been inserted to limit the matters the FWC can have regard to when conducting the BOOT, which includes:

-

- the patterns or kinds of work, or types of employment that are engaged in at the test time (or reasonably foreseeable to be engaged in);

- the overall benefits (including non-monetary benefits) an employee would receive under the proposed agreement when compared to the relevant modern award;

- giving significant weight to any views expressed by the employer, employees or a bargaining representative in regards to whether the proposed agreement passes the BOOT; and

- disregarding an individual flexibility arrangement that has been agreed into.

National Employment Standard (NES) Interaction Term

Agreements are required to include a model term (prescribed by the regulations) that explains the interaction between the NES and the agreement. If an agreement does not include the model NES interaction terms, the model term is taken to be a term of the agreement.

Variation to single enterprise agreements to cover eligible franchisee employers and their employees

A new variation mechanism has been proposed to enable an eligible franchisee employer to apply to the FWC to be covered by an existing single-enterprise agreement that covers a group of employers who operate under the same franchise.

Terminating agreements after nominal expiry date

An application to terminate an enterprise agreement that has passed its nominal expiry date cannot be made until at least three months after the agreement’s nominal expiry date.

How the FWC may inform itself

Limitations have been placed on who can provide submissions in relation to an application to approve or vary an enterprise agreement. Unless there are exceptional circumstances, the FWC may inform itself only on the basis of the following:

-

- information publically available;

- submissions made by a volunteer body;

- submissions, evidence or other information provided by (or requested from):

- in the case of an enterprise agreement: the person making the application, the employer covered by the agreement, an employee covered by the agreement or a bargaining representative for the agreement; or

- in the case of a variation: the person making the application, the employer covered by the agreement, an employee who will be covered by the agreement if the FWC approves the variation, or an employee organisation covered by the agreement.

This means that unions who are not bargaining representatives to an enterprise agreement will not be able to provide submissions unless there are exceptional circumstances for doing so.

Time limits for determining certain applications

The FWC must, as far as reasonably practicable, determine an application to approve or vary an agreement within 21 working days after the application is made.

If the FWC is unable to do so within the 21 day period, the FWC must provide notice in writing to each employer covered and each employee organisation covered (or has given notice stating that the organisation wants to be covered).

Transfer of business

A new subsection has been proposed to ensure industrial instruments do not transfer in relation to voluntary transfers of staff between associated entities.

Cessation of certain instruments

Sunsetting on 1 July 2022 of agreement-based transitional instruments, including:

-

- Division 2B State employment agreements, which are notional federal instruments that have been derived from awards and employment agreements that were in force in a state (other than Victoria) before 1 January 2010; and

- enterprise agreements and workplace determinations made during the Fair Work Act (FWA) ‘bridging period’ from 1 July 2009 to 31 December 2009.

Greenfields Agreements

A greenfields agreement that relates only to construction of a major project (ie the total expenditure of capital is at least $500 million or the Minister has made a declaration) can have a nominal expiry date of up to eight years.

If a greenfields agreement has a nominal expiry date of more than four years it must include a term that provides for an annual base rate of pay increase.

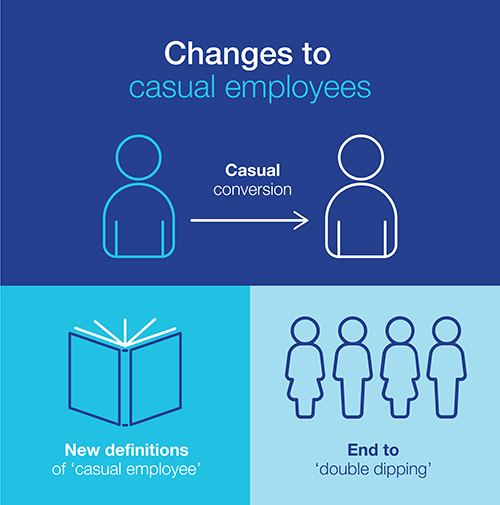

Casual employees

New statutory definition of casual employee

Definition of ‘casual employee’

It is proposed that the FWA will now define a ‘casual employee‘. This definition will override the definition of casual employee at common law.

Under transitional provisions, the statutory definition will apply in relation to an offer of employment that was made before commencement of the legislation.

A person will be considered a casual employee if:

- an offer of employment is made on the basis that the employer makes no firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work according to an agreed pattern of work for the person (this is to be determined at the time the arrangement is entered into); and

- the person accepts the offer on that basis; and

- the person is an employee as a result of that acceptance.

There is no requirement for the arrangement to be in writing, and the definition is intended to apply to informal arrangements.

The definition is intended to reflect the common law principle that the essence of casual employment is the absence of a ‘firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work according to an agreed pattern of work,’ as recently affirmed in the cases of WorkPac v Skene [2018] FCAFC 131 (Skene) and WorkPac v Rossato [2020] FCAFC 84 (Rossato).

Whether there is a firm advance commitment to continuing and indefinite work according to an agreed pattern of work will be assessed at the time the offer is made against the following factors:

-

- whether the employer can elect to offer work and whether the person can elect to accept or reject work;

- whether the person will work only as required;

- whether the employment is described as casual employment; and

- whether the person will be entitled to a casual loading or a specific rate of pay for casual employees under the terms of the offer or a fair work instrument (this term is defined in existing section 12 and includes the national minimum wage order).

This exhaustive list narrows the factors a Court can consider in making its assessment. All of the factors may be relevant and not one is determinative.

For example, if an offer of employment describes the employment as casual and includes payment of a casual loading, but provides for guaranteed hours on a continuing and indefinite basis according to an agreed pattern of work and the employee has no right to accept or reject work that is offered, the employment would not be casual.

Casual for duration of employment

Interestingly, under the proposed changes the employee’s status as a casual employee will be for the duration of their employment, or until either:

-

- the employee’s employment is converted to full-time or part-time employment under the new Division 4A of Part 2-2 of the FWA (new casual conversion provisions); or

- the employee accepts an alternative offer of employment (other than as a casual employee) by the employer and commences work on that basis.

Casual conversion

Casual conversion as part of the NES

A New Division 4A – Offers and requests for casual conversion will be included as part of the NES in the FWA.

As part of the NES, the new casual conversion provisions will be unable to be excluded or displaced by any modern award or enterprise agreement.

An employer will be required to make an offer of full-time or part-time employment to an eligible casual employee within 21 days of the employee having been employed for 12 months, subject to certain exceptions.

However, within the first 6 months, employers will be required to make offers of conversion to all existing eligible casuals, unless they have reasonable grounds not to.

‘Eligible casual employee’

An eligible casual employee is an employee:

-

- who has been employed by the employer for a period of 12 months beginning the day the employment started; and

- during at least the last six months of that period, the employee has worked a regular pattern of hours on an ongoing basis which, without significant adjustment, the employee could continue to work as a full-time employee or a part-time employee, as the case may be.

An employee cannot be converted to a fixed term contract under the proposed changes, however an employer and employee can still agree (outside Division 4A) to enter into a new fixed term arrangement.

Employment for 12 months and regular pattern of hours

Whether a person has been employed for a period of 12 months will depend on the particular circumstances. For example, if an employee works a shift on 1 December, but then does not work for the employer until 31 December the following year, it does not mean the employee has been employed for 12 months.

The term ‘regular pattern of hours’ is adopted from the FWC’s model casual conversion term. Whether an employee meets this requirement will depend on the particular circumstances and involves consideration of the pattern of hours worked during the relevant six month period.

The assessment of whether the employee worked a ‘regular pattern of hours’ is qualified by the contextual requirement that the pattern of hours must be able to be continued as a full-time or part-time employee without significant adjustment.

When must the offer to convert be made and what are the exceptions?

The offer of conversion must be made in writing within 21 days after the end of the employee’s 12 month anniversary of commencing employment (not counting the day the offer was made) and must be to convert to either:

- full-time employment, if the employee has worked the equivalent of full-time hours in the relevant 6 month period; or

- part-time employment that is consistent with the regular pattern of hours worked during the relevant 6 month period, if the employee has worked less than the equivalent of full-time hours in that period.

Once employment is converted, an employee is taken to be either a full time or part time employee (as the case may be) for the purpose of relevant laws, any applicable fair work instrument and the employee’s contract of employment.

An employer is not required to make an offer to convert to permanent employment where there are reasonable grounds for not making the offer.

Reasonable grounds include:

-

- the employee’s position will cease to exist in the period of 12 months after the time of deciding not to make the offer;

- the hours of work the employee is required to perform will be significantly reduced in that 12 month period;

- there will be a significant change in either or both of the days on which or times at which the employee will be required to perform work in that period which cannot be accommodated within the days or times the employee is available to work; or

- making the offer would not comply with a recruitment or selection process required by or under a law of the Commonwealth or a State or a Territory.

There may be other reasonable grounds on which an employer can decide not to make an offer, including those specific to their workplace or the employee’s role. Such reasonable grounds will be considered taking into account all relevant circumstances.

An employer must give written notice to a casual employee if they decide not to make an offer because:

-

- there are reasonable grounds not to make the offer; or

- the employee has been employed by the employer for a 12 month period, but does not meet the requirement to have worked a regular pattern of hours on an ongoing basis which the employee could continue to work without significant adjustment after conversion.

The written notice must be given to the employee within 21 days after their 12 month anniversary, and inform the employee:

-

- that the employer is not making an offer; and

- the reasons the employer is not making the offer, (eg if the offer is not made on reasonable grounds it must detail the details of the relevant ground).

Employee response and agreement to convert

An employee must respond to an employer’s offer of conversion with 21 days after the offer is given to the employee and indicate whether it is accepted or declined. If an employee does not respond they are taken to have declined.

If the employee accepts the offer, within 21 days the employer must give the employee written notice of:

- the employee’s new employment status (whether full-time or part-time);

- the employee’s hours of work after the conversion takes effect; and

- the day on which the conversion takes effect.

The employer must also discuss the particulars of conversion with the employee.

The conversion must take effect the first day of the employee’s first full pay period after the day the notice is given by the employer, unless otherwise agreed in writing.

Residual right to casual conversion

There will be a residual right to request casual conversion for casual employees in certain circumstances who have not received or accepted an employer offer to convert.

Eligibility criteria, grounds for refusal and formal requirements broadly reflect those applying to the obligation to offer conversion set out above.

It is also proposed that the residual right to request casual conversion will deal with failures by employers to convert casual employees, and situations in which circumstances change such that an employee may not meet eligibility criteria to convert at the relevant time, but later do meet relevant criteria.

Rights and obligations

Proposed changes to the FWA will add further protections to the general protections provisions aimed at preventing adverse action against employees relating to casual conversion.

However, it will be noted that nothing in the proposed new Division:

-

- requires an employee to convert to full-time or part-time employment; or

- permits an employer to require an employee to convert; or

- requires an employer to increase the hours of work of an employee who requests conversion to full-time or part-time employment under the Division.

It should also be noted that an employee who does not wish to convert to full-time or part-time employment (for example because they prefer greater flexibility of work and the payment of a casual loading) can remain employed on a casual basis even if they satisfy the requirements for an offer to convert.

Disputes

The amendments to the FWA will include a dispute resolution process to resolve disputes regarding casual conversion, with the FWC ultimately responsible for resolving any dispute that cannot be resolved at a workplace level.

Casual Information Statement

The FWO will prepare and publish a Casual Employment Information Statement (Statement) which employers must provide to new casual employees before, or as soon as practicable after, the employee starts casual employment.

The Statement must contain information about casual employment and requests and offers of casual conversion, including:

-

- the meaning of ‘casual employee’;

- an employer offer for casual conversion must generally be made to certain casual employees within 21 days after the employee has completed 12 months of employment;

- an employer can decide not to make an offer for casual conversion if there are reasonable grounds to do so, but the employer must notify the employee of these grounds;

- certain casual employees will have a residual right to request casual conversion; and

- the FWC may deal with disputes about the operation of that Division.

The Statement need not be given more than once in any 12-month period.

Casual employees must also still receive a Fair Work Information Statement.

No Double Dipping: addressing Skene and Rossato

Background

Many enterprise agreements and modern awards provide that a casual employee is one who is engaged and paid as such, or a similar ‘designation’ approach.

The Attorney-General’s Department has conducted an analysis of enterprise agreements and modern awards that indicates these ‘designation’ terms for identifying casual employment and the incidence of provision for payment of a casual loading is widespread.

The Department has estimated that the reliance on such terms means employers who have paid employees a casual loading in the mistaken belief that they are casual could be liable to pay those employees up to approximately $18 billion to $39 billion (over a six year period) for entitlements casual employees do not get.

In addition, as a result of the Skene and Rossato decisions, the Australian Securities and Investments Commission raised awareness of possible financial reporting considerations for entities reporting in accordance with Chapter 2M of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Corps Act).

To comply with the Accounting Standards under the Corps Act, relevant entities have to consider whether the circumstances of Skene and Rossato apply and if so, provision in their financial reports accordingly.

Under the Bill, it was estimated that the total regulatory costs of continuing with the current approach to be up to $243.8 million over a ten year period.

No Double Dipping Rule

To remedy the impact of the current approach, the Bill proposes to introduce the new definition of ‘casual employee’ (as outlined above), and a new statutory rule for offsetting amounts payable by an employer to an employee for relevant entitlements by the amount of the casual loading previously paid by the employer for the employee not having those entitlements (statutory offset rule).

The statutory offset rule is intended to apply in Rossato-type scenarios, that is where a person has been employed and paid on the understanding they were a casual employee, but is later found not to be a casual employee and a claim is made for amounts for entitlements casual employees do not receive.

It is proposed that when making orders in relation to such a claim, a court must reduce any amounts payable by the employer for relevant entitlements against casual loading amounts paid to the person.

The statutory offset rule will apply if:

-

- a person is employed by an employer in circumstances where the employment is described as casual employment; and

- the employer pays the person an identifiable amount (the loading amount) to compensate the person for not having one or more relevant entitlements (as defined) during a period (the employment period); and

- during that period, the person was not a casual employee; and

- the person (or another person for the benefit of the person) makes a claim to be paid an amount for one or more of those entitlements with respect to the employment period.

The loading must be an identifiable amount paid as compensation for the absence of the relevant entitlements during the employment period. As the loading must be clearly identifiable, the statutory offset rule will not include a situation where an employee is paid a flat hourly rate and it is not clear what component is the casual loading.

A court, when making orders in relation to the claim can reduce any amount payable by the employer for the relevant entitlements (the claim amount) by an amount equal to the loading amount, but not below nil.

The court may reduce the claim amount by an amount equal to a proportion of the loading amount the court considers appropriate, having regard only to:

-

- if a term of the fair work instrument or contract of employment under which the loading amount is paid specifies the relevant entitlements the loading amount is compensating for and specifies the proportion of the loading amount attributable to each such entitlement – that term (including those proportions); or

- if such a term specifies the relevant entitlements the loading amount is compensating for but does not specify the proportion of the loading amount attributable to each such entitlement – that term, and what would be an appropriate proportion of the loading amount attributable to each of those entitlements in all the circumstances; or

- if paragraph (a) or (b) does not apply – the NES entitlements listed below on what would be an appropriate proportion of the loading amount attributable to each of those entitlements in all the circumstances.

A relevant entitlement refers to an entitlement under the NES, fair work instrument or contract of employment to any of the following:

-

- paid annual leave;

- paid personal/carer’s leave;

- paid compassionate leave;

- payment for absence on a public holiday;

- payment in lieu of notice of termination;

- redundancy pay.

It should be noted that if an employment contract (or other relevant instrument) lists that casual loading is paid instead of some entitlements (for example, annual and personal leave), but the employee claims for notice and redundancy pay, the court will be unable to offset the casual loading against the claim for notice and redundancy pay.

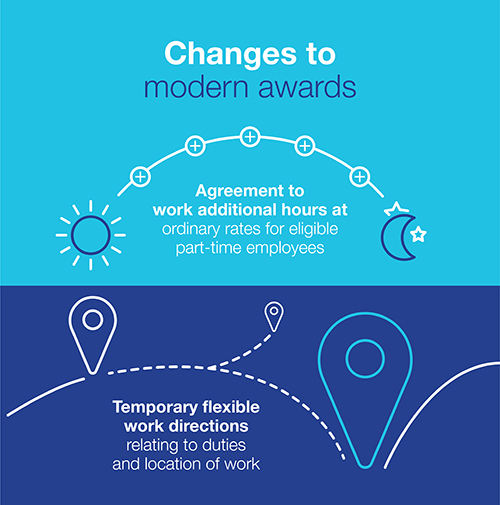

Modern awards

Agreement for part-time employees to work additional agreed hours

New flexibilities to allow employers and eligible part-time employees to agree to work additional hours at ordinary time rates of pay through entering into a simplified additional hours agreement.

To be eligible, employees must be covered by one of the below modern awards (identified modern awards) and the part-time employee’s ordinary hours of work must be at least 16 hours per week (or at least 16 hours per week averaged in accordance with the relevant modern award provisions).

Identified modern awards

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Not agreeing to a simplified additional hours agreement is a workplace right

Employers cannot force eligible part-time employees to enter into (or termination/not terminate) simplified additional hours agreements.

The simplified additional hours agreement

A simplified hours agreement must identify the additional agreed hours to be worked and must be entered into before it commences. While there is no requirement for a simplified additional hours agreement to be in writing, employers are required to keep a written record of the agreement and provide a copy to the employee if requested.

The new provision provides for safeguards including a minimum engagement period of at least three hours, and for the arrangement not to exceed any maximum number of consecutive days an employee may be required to work as prescribed by the relevant modern award.

A simplified additional hours agreement may be terminated by either party giving at least seven days written notice of the termination date, or mutually in writing at any time.

Flexible work directions

New temporary flexible work directions provisions provide employers with additional flexibilities to give an eligible employee a direction about the duties to be performed by the employer or the location of the employee’s work. Directions made under this provision cease to have effect after the end of the period of two years beginning on the day the new provision comes into effect or if it is withdrawn, revoked or replaced by the employer.

To be eligible employees must be covered by one of the identified modern awards outlined above.

Flexible work duties

An employer can direct an eligible employee to perform any duties that are within their skill and competency provided that the duties are safe, the employee holds any relevant licence or qualification to perform the duties, and the duties are reasonably within the scope of the employer’s business operations.

Flexible work location direction

An employer can direct an eligible employee to perform duties at a place that is different from the employee’s normal place of work (including the employee’s home) if the place is suitable for the employee’s duties and the performance of the duties at the place is safe and reasonably within the scope of the employer’s business operations.

If the directed location is not the employee’s home, the location must not require the employee to travel a distance that is unreasonable in the circumstances (including circumstances surrounding COVID-19).

Requirements

For a flexible work direction to have effect it must:

-

- not be unreasonable in all the circumstances. For example, if a direction impacts on an employee’s caring responsibilities it may be considered unreasonable in the circumstances; and

- be a necessary part of a reasonable strategy to assist in the revival of the employer’s enterprise based on the information before the employer.

Employer’s must abide by consultation obligations similar to those required for providing a JobKeeper direction (ie written notice must be provided at least three days before the direction is given unless a lesser notice period has been mutually agreed to, and the employee must be consulted prior to the direction being given).

Flexible work directions cannot reduce an employee’s hourly base rate of pay.

Compliance and enforcement

Introducing a new criminal offence for employers who dishonestly engage in a systematic pattern of underpaying employees

It will be a criminal offence for an employer to dishonestly engage in a systematic pattern of underpaying one or more employees. This does not apply to one-off underpayments, genuine mistakes or miscalculations, as the conduct must be intentional, dishonest and systematic.

For an individual, the maximum penalty is up to four years imprisonment or up to 5000 penalty units (currently $1.11 million) or both. For a corporation, the maximum penalty is up to 25,000 penalty units (currently $5.55 million).

Introducing new remuneration-related contraventions and civil penalties

‘Remuneration-related contraventions’ will include:

-

- a contravention of a civil remedy provision that relates to:

- minimum wages;

- equal remuneration;

- method and frequency of payment;

- unreasonable requirements to spend or pay certain amounts; or

- guarantee of annual earnings; and

- a contravention of a civil remedy provision that relates to:

- the underpayment of wages, or other monetary entitlements of employees;

- the unreasonable deduction of amounts from amounts owed to employees;

- the placing of unreasonable requirements on employees to spend or pay amounts paid, or payable to employees; or

- the method or frequency of amounts payable to employees in relation to the performance of work.

- a contravention of a civil remedy provision that relates to:

| If… | The pecuniary penalty must not be more than… |

|

(a) the person is an individual; and (b) the contravention is a remuneration-related contravention but not a serious contravention | 90 penalty units (currently $19,980). |

|

(a) the person is a body corporate; (b) the contravention is a remuneration-related contravention but not a serious contravention; and (c) the body corporate was a small business employer when the application for the order was made. | 450 penalty units (currently $99,900). |

|

(a) the person is a body corporate; (b) the contravention is a remuneration-related contravention but not a serious contravention; and (c) the body corporate was not a small business employer when the application for the order was made. |

The greater of: (a) 450 penalty units (currently $99,900); or (b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit of the contravention – two times the value of the benefit. |

|

(a) the person is a body corporate; (b) the contravention is both a remuneration-related contravention and a serious contravention; and (c) the body corporate was not a small business employer when the application for the order was made. |

The greater of: (a) 3,000 penalty units (currently $666,000); or (b) if the court can determine the value of the benefit of the contravention – three times the value of the benefit. |

Increasing civil penalties for sham arrangements and failure to comply with compliance notices by 50%

The maximum penalty for sham contracting contraventions will increase by 50% from 60 to 90 penalty units for an individual (currently $19,980) and up to five times higher for bodies corporate (currently $99,900).

Similarly, the maximum penalty for failure to comply with a compliance notice issued by a Fair Work Inspector will increase by 50% from 30 penalty units to 45 penalty units for an individual (currently $9,990) and up to five times higher for a body corporate (currently $49,950).

The jurisdictional limit for small claims will increase from $20,000 to $50,000, meaning more applicants will have access to the simpler and more cost effective enforcement process under the small claims jurisdiction. A court will also be able to award a successful applicant their filing fee from the respondent.

Courts will have the power to refer small claims matters to the FWC for conciliation and, if conciliation is unsuccessful, the FWC to be able to arbitrate the matter with consent of the parties

A court will have the power to refer any matter in the small claims jurisdiction for conciliation by the FWC if the court considers this appropriate, having regard to:

-

- the stage the proceedings have reached since the commencement of the proceedings;

- the complexity of the matters in dispute, including questions of law that might arise; and

- whether conciliation would be effective in resolving the matters in dispute in the proceedings.

The FWC will also have the power arbitrate small claims matters by consent of the parties if conciliation has been unsuccessful and a certificate to that effect has been issued by the FWC.

New offence which prohibits employers publishing (or causing to be published) job advertisements with pay rates specified at less than the relevant national minimum wage

A new offence will be introduced which prohibits employers (including prospective employers) from advertising, or causing to be advertised, a job with the employer specifying a rate of pay less than the national minimum wage or special national minimum wage.

The offence will be a civil remedy provision. Where there is a contravention, the maximum penalty will be 60 penalty units for individuals (currently $13,320) and up to five times higher for bodies corporate (currently $66,600).

Requiring the FWO to publish information relating to the circumstances in which enforcement proceedings will be commenced or deferred

The FWO will be required to publish information relating to the circumstances in which the FWO will commence proceedings in accordance with the FWA or, alternatively, defer proceedings to deal with suspected non-compliance through other compliance mechanisms.

This amendment provides employers with greater certainty about possible enforcement outcomes to further encourage identification of remuneration-related and other contraventions.

Codifying the factors which the FWO may take into account in deciding whether to accept an enforceable undertaking

The Bill codifies the factors which the FWO may take into account in deciding whether to accept an enforceable undertaking as an alternative to court action including:

-

- whether the person made a voluntary disclosure of the contravention to the FWO;

- whether the person has demonstrated a willingness to address the contravention’s impact;

- whether the person has demonstrated a willingness to fully cooperate with the FWO in relation to the contravention;

- whether the contravention was the result of an honest mistake or inadvertence by the person;

- the nature and gravity of the contravention;

- the circumstances in which the contravention occurred; and

- the person’s history of compliance with the FWA.

What comes next?

The Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations, Christian Porter has said: “It should also be said that the introduction of the Bill today is by no means the end of the consultation process, with a Senate Committee likely to examine the legislation in detail over the coming months.”

While the Morrison government has signalled its clear intention to continue to consult with key stakeholders, the Bill has already drawn the ire of the union movement who have been quick to criticise some of the more contentious aspects of the proposed legislation. Although the Bill is likely to be subject to further amendments before it is passed, it is a clear indication from the Morrison government that industrial relations reform is back on the agenda for 2021 and beyond.